Why Starting Young and Getting Proper Training Is the Key to Investment Success

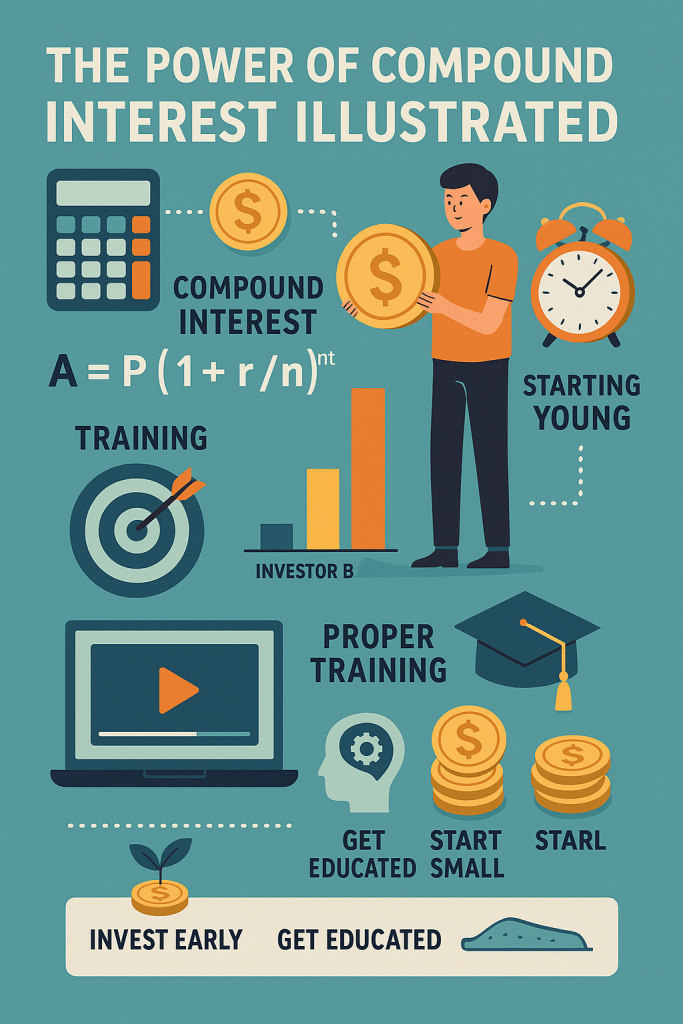

Investing can at first seem like an intimidating endeavor: charts, jargon, and the ever-present risk of losing money can deter even the most disciplined savers. Yet beneath the surface of this complex-sounding arena lies a simple, potent concept that has powered the exceptional wealth trajectories of countless individuals throughout history: compound interest. In its essence, compound interest represents the process by which an investment’s returns themselves generate further returns, accelerating growth exponentially over time. As financial professionals frequently emphasize, the sooner one begins investing—even with modest sums—the more significant the impact of compounding. However, this principle does not grant immunity to rash decision-making. Investing, like any worthy profession, requires foundational knowledge, ongoing education, and disciplined execution.

This article explores, in depth, the dynamics of compound interest, why beginning to invest at a young age confers such a powerful advantage, how small sums can flourish when entrusted to compounding growth, and why formal or self-directed education in finance is indispensable before embarking on the journey. Our aim is to provide a comprehensive, professional examination of these themes, equipping both nascent and seasoned readers with the insights needed to leverage compound interest effectively while recognizing the responsibility that comes with managing one’s capital.

1. What Is Compound Interest?

At its core, compound interest is the process by which an investment’s gains are reinvested so that those gains also earn returns. In contrast to simple interest—where interest is calculated solely on the initial principal—compound interest ensures that “interest on interest” becomes a driving force behind exponential wealth accumulation.

- Simple Interest: Calculated only on the original principal.

- Compound Interest: Calculated on both the original principal and on accumulated interest from previous periods.

To illustrate this distinction:

- Suppose you invest $10,000 at an annual simple interest rate of 5%. After one year, you earn $500 in interest. For each subsequent year, you continue to earn $500 annually, regardless of how much time passes.

- Conversely, if you invest $10,000 at an annual compound interest rate of 5% (compounded yearly), your account balance evolves as follows:

- Year 1: $10,000 × 1.05 = $10,500

- Year 2: $10,500 × 1.05 = $11,025

- Year 3: $11,025 × 1.05 = $11,576.25

- …and so on.

Over a ten-year span, the compounding effect yields a balance of approximately $16,288, whereas simple interest yields only $15,000. The gap widens in longer horizons. This self-reinforcing mechanism—where interest itself becomes a source of new interest—lies at the heart of compounding’s extraordinary power.

2. The Mathematics Behind Compound Interest

Although many investors never consult the precise formulas, understanding the mechanics of compound interest mathematically underpins disciplined decision-making. The standard formula for compound interest (when interest compounds at discrete intervals) is:

A = P \times \left(1 + \frac{r}{n}\right)^{n \times t}

Where:

- A = the future value of the investment/loan, including interest.

- P = the principal (initial amount of money).

- r = the annual nominal interest rate (as a decimal, e.g., 0.05 for 5%).

- n = the number of times that interest is compounded per year.

- t = the time the money is invested for, in years.

Key Observations:

- Frequency Matters: When compounding frequency increases (e.g., quarterly, monthly, daily), the effective annual yield edges upward. For instance, at 5% annual nominal rate:

- Compounded annually (n = 1): Effective annual rate = 5%

- Compounded quarterly (n = 4): (1 + 0.05/4)^{4} – 1 \approx 5.0945\%

- Compounded monthly (n = 12): (1 + 0.05/12)^{12} – 1 \approx 5.1162\%

- Exponential Growth: Because the formula involves an exponent (n \times t), each additional period of compounding (or additional year) causes growth to accelerate.

- Doubling Time (“Rule of 72”): A heuristic many investors memorize is the “Rule of 72.” By dividing 72 by the annual interest rate (in percent), one gets a rough estimate of how many years it takes for an investment to double. For a 7% return: 72 / 7 \approx 10.3 \text{ years} While not exact—particularly at very high or very low rates—this rule provides an intuitive benchmark.

3. Why Starting Early Matters: The Time Advantage

In any discussion of compounding, time is the most critical variable. The longer funds remain invested, the more compounding can work its magic. Even modest contributions, consistently invested over decades, can yield substantial sums. Below, we compare two hypothetical investors to illustrate this principle:

- Investor A begins investing $2,000 per year (at the end of each year) at age 25 and continues until age 35 (10 years of contributions) into a portfolio yielding an average annual return of 7%. Afterward, Investor A stops contributing and lets the capital grow (still compounding at 7%) until age 65 (30 more years without new contributions).

- Investor B does not invest initially but begins contributing $2,000 per year at age 35 and continues until age 65 (30 years of contributions), at the same 7% annual return. We want to compare their balances at age 65.

Calculation Breakdown:

- Investor A (Contribute from 25 to 35; then let it compound until 65):

- During years 25–35, each annual $2,000 contribution compounds for varying periods until age 35. The balance at age 35, B_{35}, can be computed as the future value of an annuity: B_{35} = 2{,}000 \times \frac{(1.07)^{10} – 1}{0.07} \approx 2{,}000 \times 13.8164 \approx \$27{,}632.80

- From age 35 to 65 (30 years), this $27,632.80 compounds at 7%: B_{65} = 27{,}632.80 \times (1.07)^{30} \approx 27{,}632.80 \times 7.6123 \approx \$210{,}360

- Investor B (Contribute $2,000 per year from 35 to 65):

- The future value at age 65 of $2,000 annual contributions over 30 years at 7%: B_{65} = 2{,}000 \times \frac{(1.07)^{30} – 1}{0.07} \approx 2{,}000 \times 94.461 \approx \$188{,}922

Despite investing for only 10 years (versus 30 years), Investor A ends up with more capital at retirement than Investor B—specifically, about $210,360 versus $188,922. This edge comes entirely from the extra decades of compounding on initial contributions. The moral is unmistakable: every year earlier that funds stay invested dramatically amplifies end wealth.

4. Starting Young Even with Limited Capital

A common objection among young adults is, “I don’t have enough money to invest now; I will wait until I save a larger sum.” However, waiting can prove far more costly than investing small amounts immediately. Several factors underscore why small, regular investments made early can outperform larger, later ones:

- Behavioral Discipline and Habit Formation Investing small sums inculcates a saving and investing mindset. Consistently redirecting even a modest portion of one’s paycheck—say, 5%—into an investment vehicle fosters prudent financial habits that tend to endure and expand over time.

- Dollar‐Cost Averaging (DCA) Investing modest amounts periodically (e.g., monthly or quarterly) harnesses the principle of dollar‐cost averaging. When markets fluctuate, this approach provides the benefit of buying more shares when prices dip and fewer when prices rise, effectively reducing the average purchase cost over time. For a young investor without large sums, DCA is a practical way to build a position gradually while mitigating the emotional impact of market timing.

- Psychological Benefits of Early Involvement Even if initial portfolio values are small, early involvement in the markets helps an investor learn firsthand how markets behave—periods of volatility, drawdowns, and fleeting rallies. These lessons, absorbed in smaller “sandbox” environments, prepare the investor mentally for larger sums later on. Conversely, someone who waits until they accumulate substantial savings may encounter market corrections or volatility that can be emotionally jarring if they have no prior investing experience.

- Harnessing Compound Growth on Any Principal Let’s say a 21-year-old starts with just $1,000 and adds $100 monthly to an index fund averaging a conservative 6% annualized return. By age 65, that initial $1,000 plus the monthly contributions could grow to a six-figure balance—purely by granting time for compounding. Although $100 monthly may seem inconsequential compared to larger contributions later, the multiplying effect of nearly four and a half decades of growth will be substantial.

- The Opportunity Cost of Delay Consider a 30-year-old who contemplates waiting five years to accumulate $10,000 before investing. If that $10,000 could instead have been deployed at age 25—or even a smaller initial seed invested at 25—the next five years of compounding results cannot be recouped. Over long horizons, these early years can constitute a significant fraction of total investment returns.

5. The Crucial Role of Financial Education

While the virtues of early investing and compounding are compelling, they must be tempered by a realistic understanding of investment products, market cycles, and risk management. Recognizing that “investing is like a craft” underscores the need for proper training. Below, we explore why education is non‐negotiable and propose avenues for aspiring investors to build knowledge.

5.1. Understanding Risk Versus Reward

Every investment carries risk—market risk, liquidity risk, credit risk, inflation risk, among others. Novice investors might be tempted by high‐promised returns (e.g., speculative assets, “hot tips,” or leveraged products) without fully grasping the potential downside. Through structured education, one learns to:

- Distinguish between asset classes (equities, bonds, real estate, commodities, alternative investments).

- Analyze historical volatility and drawdown patterns.

- Assess one’s own risk tolerance and align it with an appropriate portfolio allocation.

- Implement proper diversification to mitigate idiosyncratic risks.

Without this foundation, early investment efforts—no matter how well‐intentioned—can be undone by ill‐advised bets.

5.2. Evaluating Investment Vehicles

Not all investments compound at the same rate or with the same predictability. A 7% historical return on the S&P 500, for instance, masks the reality that certain years saw double‐digit losses while others experienced double‐digit gains. Aspiring investors should learn to:

- Read fund prospectuses and fee structures: Understand expense ratios, turnover costs, and how fees erode long‐term returns.

- Compare passive versus active approaches: Examine whether actively managed mutual funds justify higher fees by outperforming benchmarks over complete market cycles.

- Appreciate the trade‐off between liquidity and return: Real estate or private equity might offer higher return potential but at the cost of lower liquidity and longer lock‐up periods.

5.3. Mastering Fundamental and Technical Analysis (When Appropriate)

While a broad, passive allocation can suffice for many long‐term investors, those seeking to outpace passive benchmarks will require analytical skills:

- Fundamental Analysis: Evaluating companies’ financial statements, assessing management quality, and discerning valuation metrics (P/E, EV/EBITDA, etc.).

- Technical Analysis: Learning chart patterns, volume indicators, and sentiment gauges—particularly relevant for traders or investors looking to time entry and exit points more precisely.

5.4. Behavioral Finance and Emotional Discipline

Academic and professional research in recent decades has illuminated how cognitive biases—overconfidence, herding, loss aversion—can derail even the most well‐constructed strategy. Educational programs, whether through college coursework, online platforms, or self‐study, should include:

- Awareness of common biases and techniques to mitigate them.

- Developing an investment policy statement (IPS) to anchor decisions.

- Simulated trading platforms (paper trading) to practice without risking real capital, thus learning firsthand how emotions respond when positions turn negative.

5.5. Practical Pathways for Financial Education

- Academic Coursework and Degrees Degrees in finance, economics, or business administration provide structured curricula. Courses typically cover microeconomics, macroeconomics, corporate finance, portfolio management, and derivatives. For someone balancing work or other commitments, part‐time or online degree programs offer flexibility.

- Professional Certifications Credentials such as the Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) designation represent rigorous, multi‐year commitments but afford deep knowledge in portfolio management, ethical standards, and equity/bond analysis. For those interested in personal finance or financial planning, Certified Financial Planner (CFP) certification provides a strong grounding in retirement planning, insurance, tax strategies, and behavioral finance.

- Online Platforms and MOOCs Many reputable universities and educational providers (e.g., Coursera, edX, Khan Academy) offer courses on investment fundamentals, valuation techniques, and quantitative finance. Interactive modules, video lectures, and quizzes can turn abstract concepts into digestible knowledge.

- Books and Thought Leaders Time‐tested classics such as Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor, Burton G. Malkiel’s A Random Walk Down Wall Street, or John C. Bogle’s Common Sense on Mutual Funds serve as foundational texts. More contemporary works on behavioral finance—like Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow or Robert Shiller’s Irrational Exuberance—help bridge the gap between theory and practical market dynamics.

- Mentorship and Networking Engaging with experienced investors—through professional associations, alumni networks, or local investment clubs—affords practical, real‐world insights. Mentors can share lessons learned, cautionary tales, and tips that no textbook can fully capture.

5.6. Our Training Programs for Aspiring Investors

To complement the pathways described above, we offer a comprehensive suite of courses—both free and paid—designed to guide you from foundational concepts to advanced investment strategies. Our programs include:

- Introductory Workshops (Free): Focused on basic principles of budgeting, saving, and the earliest steps in opening an investment account. Ideal for complete beginners who need a solid starting point.

- Fundamentals of Finance (Free & Premium Tracks): Covers the essentials of financial statements, risk management, and portfolio construction. In the free track, you gain access to core lectures and quizzes; in the premium track, you receive deeper case studies, one-on-one mentorship, and graded assignments.

- Advanced Investment Strategies (Paid): For students who have mastered the fundamentals, this course delves into sector analysis, derivatives, alternative investments, and hedge fund techniques. Each module includes live webinars with industry experts and access to a simulated trading platform.

- Behavioral Finance and Emotional Discipline (Free & Paid): Teaches you how to recognize cognitive biases, build an investment policy statement, and develop emotional resilience for market volatility. The paid version offers personalized coaching sessions to apply these principles to your own portfolio decisions.

- Ongoing Community Support: All enrolled students (both free and paid) can participate in our monthly Q&A webinars, join moderated discussion forums, and attend quarterly investment strategy meetups—online or in person, depending on your location.

By following our structured curriculum, you can ensure that you’re not just reading about compounding and investing, but that you’re also applying these principles under the guidance of seasoned professionals. Our ultimate goal is to transform committed learners into confident, self-sufficient investors who know how to harness compound interest responsibly to achieve long-term financial goals.

6. Practical Steps to Begin Investing Responsibly

Assuming the reader is convinced of compound interest’s power and has taken steps to educate themselves (including through our courses), what follows is a structured roadmap for getting started:

6.1. Define Clear Financial Goals

- Short‐Term Goals (0–5 years): Emergency fund accumulation, down payment for a home, vacation fund, etc.

- Medium‐Term Goals (5–15 years): Funding a child’s education, starting a business, significant home improvements.

- Long‐Term Goals (15+ years): Retirement, legacy planning, generational wealth transfer.

Each goal will have different time horizons and risk tolerances. For example, funds earmarked for a down payment in three years should be invested more conservatively than retirement savings with a 30‐year horizon.

6.2. Establish an Emergency Fund

Before allocating capital to the markets, ensure you have a cash cushion (“emergency fund”) equivalent to 3–6 months of living expenses. This buffer prevents the need to prematurely liquidate investments during market downturns, preserving the compounding process.

6.3. Choose an Appropriate Investment Vehicle

- Tax‐Advantaged Accounts:

- In the U.S.: 401(k), IRA, Roth IRA, 529 plans.

- In other jurisdictions (e.g., U.K.): Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs).

- In Spain: Plan de Pensiones, Plan Ahorro 5, etc.

- Brokerage Accounts: For capital not earmarked for retirement, brokerage or custodial accounts permit investment in stocks, bonds, ETFs, mutual funds, and other securities without withdrawal restrictions (though capital gains taxes apply).

- Robo‐Advisors: Automated platforms allocate portfolios based on risk questionnaires, systematically rebalancing to maintain intended asset mixes. Fees are typically lower than traditional advisors, making them attractive to young investors with limited capital but a desire for professional management.

6.4. Determine an Asset Allocation Strategy

Deciding how much to allocate to equities, fixed income, cash equivalents, and alternative assets hinges on one’s time horizon and risk tolerance. As a rule of thumb:

- Longer Horizons (20+ years): Higher equity allocations (e.g., 80–90%) to maximize growth potential.

- Medium Horizons (5–15 years): Balanced allocations (e.g., 60% equities, 40% bonds).

- Shorter Horizons (0–5 years): Conservative allocations (e.g., 20–40% equities; remainder in high‐quality bonds or cash).

Age‐based allocation “rules” (e.g., “Subtract your age from 100 to obtain % in equities”) can serve as a starting framework, though investors should adjust for personal circumstances, risk appetite, and financial goals.

6.5. Implement Dollar‐Cost Averaging (DCA)

Rather than attempting to “time the market,” allocate fixed sums periodically (e.g., monthly). This disciplined, mechanical strategy can smooth out purchase prices and help investors stay committed during market downturns. Over long periods, it often outperforms lump‐sum investing for those wary of market peaks.

6.6. Mind Fees, Taxes, and Hidden Costs

- Expense Ratios: Index funds and ETFs often have expense ratios below 0.10%, whereas actively managed mutual funds may charge 0.75–1.50% or more. Over decades, high fees can erode a large portion of compounding gains.

- Transaction Costs: Choose brokers offering free or low‐cost trades, especially for small, periodic investments.

- Tax Efficiency: Understand the tax treatment of dividends, capital gains, and interest in your jurisdiction. Using tax‐efficient vehicles and holding periods (long‐term vs. short‐term capital gains) can significantly enhance net returns.

6.7. Cultivate a Long‐Term Mindset

Markets are inherently volatile in the short term. An investor who sees a 10% drawdown early in their journey might panic and exit, crystallizing losses. Recognize that:

- Upswings and Downswings Are Normal: Historically, markets have recovered from corrections and bear markets, eventually reaching higher highs.

- Staying Invested Is Paramount: Missing even a handful of the best return days can markedly reduce lifetime returns. A study of S&P 500 returns between 1980 and 2020 shows that missing the ten best days slashes returns by more than half.

- Periodic Rebalancing: As allocations drift due to varying asset performance, rebalancing ensures the portfolio’s risk profile remains aligned with original targets.

6.8. Leverage Technology and Tools

- Portfolio Trackers and Aggregators: Personal finance apps can consolidate investment holdings, track performance, and monitor asset allocation in real time.

- Financial Newsletters and Market Analysis: Subscribing to reputable newsletters can help investors stay informed of macroeconomic trends, earning reports, and geopolitical events that could impact markets.

- Automated Alerts: Set notifications for significant portfolio drifts, major market moves, or news related to core holdings.

7. Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Chasing High Returns without Understanding Risk Tempting though “hot” investments—cryptocurrencies, speculative biotech startups, or niche speculative plays—can be, it is crucial to assess the underlying risk‐reward profile. A disciplined investor asks:

- What is the probability of permanent capital loss?

- Do I understand the business model, balance sheet, competitive landscape?

- Is this investment a small percentage of my total portfolio, or am I overexposed?

- Failing to Diversify Concentrating wealth in a single sector, company, o r asset type can magnify both gains and losses. A diversified portfolio—spreading capital across equities, fixed income, and (where suitable) alternative assets—reduces idiosyncratic risk. For instance, a sudden industry‐specific shock (e.g., regulatory crackdown on fintech) can cripple undiversified portfolios.

- Being Swayed by Market “Noise” Short‐term news cycles, sensational headlines, and social media “gurus” can create FOMO (fear of missing out) or panic. A well‐educated investor recognizes that daily price movements often have little correlation with long‐term fundamentals.

- Neglecting Regular Portfolio Reviews While a passive, “set‐and‐forget” approach has merits, life circumstances (marriage, addition of children, career changes) can alter risk tolerance and time horizons. Conducting semi‐annual or annual reviews ensures the investment strategy remains aligned with evolving goals.

- Ignoring Inflation and Real Returns A portfolio generating a nominal 7% return in an environment where inflation runs at 4% yields only a 3% real return. Over extended periods, failing to account for inflation can leave one with less purchasing power than anticipated. Consequently, allocating part of the portfolio to assets that historically outpace inflation (e.g., equities, real estate, inflation‐protected bonds) is essential to preserve and grow real wealth.

8. Real‐World Illustrations

To crystallize the abstract, consider two illustrative scenarios.

8.1. Scenario 1: The 20‐Year‐Old with Modest Means

- Background: Graduated from university with $5,000 in savings at age 20. Secures a job reaching $30,000 per year within two years.

- Investment Plan:

- At age 20: Invest the $5,000 as a lump sum into a low‐cost S&P 500 index fund.

- Ages 21–30: Invest $200 per month (≈8% of take‐home pay) consistently into the same index fund.

- Ages 31–65: Increase contributions gradually (matching pay raises) to $500 per month by age 31, $800 by age 40, $1,200 by age 50, and $1,500 by age 60; all invested in a broadly diversified, equity‐heavy portfolio.

Assuming a conservative 6.5% annualized return (inclusive of dividends reinvested), by age 65, this investor’s portfolio could exceed $1 million.

8.2. Scenario 2: The 35‐Year‐Old Delayed Investor

- Background: Decides to wait until age 35 to “have enough” money before investing. Accumulates $30,000 in savings but leaves it in cash or low‐yield savings accounts (<1% interest) from ages 25 to 35.

- Investment Plan Starting at 35: Invest $30,000 lump sum into the same S&P 500 index fund. Then, contribute $500 per month from ages 35–65, gradually increasing to $1,500 per month by age 65.

- Outcome: Even though this investor starts with triple the initial capital ($30,000 vs. $5,000) and higher monthly contributions later, the final portfolio by age 65 is substantially smaller—owing primarily to a decade lost to compounding.

While exact numbers depend on market fluctuations, the relative comparison consistently shows that the earliest decades of compounding are the most potent. Every additional year in the market adds cumulative growth on growth, which compounding multiplies.

9. Key Takeaways and Best Practices

- Start as Soon as Feasible: There is almost no scenario in which delaying by even a single year justifies waiting to accumulate larger initial capital. The time value of money and compounding advantages outweigh the small gain from a marginally larger principal later.

- Educate Before You Invest: Treat investing as you would a craft or profession. Allocate time to learn about market structure, asset classes, risk management, and behavioral pitfalls. The cost of being uninformed or under‐prepared can vastly exceed the fees paid for a course, book, or professional consultation.

- Leverage Low‐Cost, Tax‐Efficient Vehicles: Maximize the net effect of compounding by minimizing fees and taxes. Whenever possible, use accounts that defer or eliminate annual taxes on gains (e.g., retirement accounts, tax‐advantaged savings plans).

- Build a Sustainable, Diversified Portfolio: Resist the urge to chase “hot tips.” Instead, focus on a strategically diversified allocation that aligns with your time horizon and risk appetite. Passive indexation often offers lower cost, transparent performance, and broad market exposure.

- Maintain Consistency Through Market Cycles: Dollar‐cost averaging and a long‐term mindset reduce the temptation to engage in market timing. Remember that staying invested—even during drawdowns—often yields better outcomes than sitting on the sidelines in cash.

- Periodically Reassess Goals and Allocations: Life changes (marriage, parenthood, career transitions, approaching retirement) necessitate adjustments to both goals and risk profiles. Schedule annual or semi‐annual portfolio reviews to ensure alignment.

- Keep Learning and Adapting: Financial markets and products evolve. What was optimal a decade ago may no longer be best practice today. Continue reading new books, attending seminars, and following reputable financial news to stay informed.

10. Conclusion

Compound interest stands as arguably the most powerful principle in personal finance. Its exponential nature underscores the extraordinary advantage conferred by time in the market. For young investors in particular, even modest contributions—earned from part‐time jobs, internships, or early career salaries—can burgeon into significant portfolios over decades when left to compound. Yet, this advantage does not entail recklessness; rather, it demands education, discipline, and prudence.

Investing is not merely about deploying capital; it is a craft requiring mastery of fundamental analysis, an understanding of risk, and emotional fortitude in the face of market volatility. By committing to ongoing education—through formal coursework, self‐study, mentorship, or professional certifications—investors empower themselves to make informed decisions. When combined with an early start, a methodical approach to asset allocation, and diligent attention to fees and taxes, compound interest can transform modest savings into a robust financial foundation for life’s ambitions.

Ultimately, the most critical step is the first one: opening that investment account, making a small deposit, and committing to learn. Because in the world of investing, time is the investor’s greatest ally—and the clock starts ticking the moment you embrace compound interest as an ally rather than an abstract concept. Start today, invest prudently, and watch how even modest sums can, over time, become the bedrock of long‐term financial security and prosperity.